Keeill number thirty eight.

It may also be remarked, that besides Barrows, other reliques of antiquity of a different kind, are thickly scattered all over the Island, namely, the Kihls or small Kirks of the early Christians. These are merely small enclosed spaces, containing some mounds or rubbish, and are so numerous that it is said that every treen anciently possessed one. They appear to have been a kind of domestic chapels, and are said to have been visited occasionally by itinerating monks. To this day, tradition affixes the chaplaincy of one in Braddan named Kiel-Albin, to the proprietor of a neighbouring farm, Awhallyon. But in general, they are now entirely forgotten, and only superstitiously venerated as containing the remains of the dead, for they have all been used as burying places. As an example of one, Kiel-Vael, or Michael, which signifies Kirk Michael. situated on the top of Balladoole hill, may be pointed out as occurring on this road. Another, near the Douglas road, may be seen on passing Bulreinny hill, Mount Murray. (Oswald, 1831, ‘Isle of Man New Guide’)

I have put off writing this post for a while as unlike the other posts I have only one photo of the keeill site, somewhere I found myself particularly uninspired by, especially as it took us two attempts to find it. I think we were expecting more than the solitary stone on the edge of a golf course which is all that marks the location in 2016. The stone is thought to have been in place for many years and was possibly placed there to keep the plough away from the site, either to preserve it or to preserve the plough from large stones that may cause damage.

The purpose of this blog is to document all the ‘Keeills’ on the Isle of Man with existing remains in 2016 and under that description, ‘Speke Keeill’ does not warrant a post. However, what was found during an investigation by Time Team and Wessex Archaeology in 2006 makes Speke Keeill very much deserving of a mention.

The keeill site is on the land of the Mount Murray Golf Club, sitting very close to the Speke Lane boundary, the burial site continues on the other side of the lane on Speke Farm land. Marstrander in ‘Treen og Keeill’ (1937) mentions Speke in his list of keeills on the Island but gives no measurements of the building or a known dedication.

Mount Murray is a hill just outside of Douglas, in the past it was sometimes known as ‘The Mount’ and earlier as ‘Cronk Glass’ meaning ‘Green Hill’ (Gill, 1929. ‘A Manx Scrapbook). The earliest name for the hill seems to have been ‘Ais Hólt’ which means ‘Holt’s Hill’, Holt was a Norse surname (Kneen, 1925, ‘Place names of the Isle of Man’).

In 1717, a Dublin Merchant, Richard McGwire, applied to enclose an area of common land known as ‘being the mountain called Ash hold’ and started to build a house there. Unfortunately, he got in to debt and the estate was sold a couple of times and rented out (at one stage to Sir Wadsworth Busk, attorney general of the Island 1774-1797′) before it was bought by Lord Henry Murray in 1793 (information taken from Manx Notebook).

‘The house is elegant: and Sir Wadsworth’s fine taste endeavoured to embellish some of the neighbouring fields; but the sterility of the soil, in a great measure, has frustrated every attempt. Yet, in this retirement Sir Wadsworth devotes himself to the pursuits of literature and the enjoyment of domestic virtues.

At a little distance from Newtown, on the top of a mountain, Sir Wadsworth erected a pillar inscribed to the Queen, in commemoration of his Majesty’s recovery in 1789; which has little to recommend it to a traveller’s attention, except the loyalty it expresses. To the fishermen on this side of the island, it however proves, from its elevation, an excellent sea-mark.’ (Robertson, 1794, ‘A Tour Round the Isle of Man’)

The mound where Sir Wadsworth erected his pillar still exists although the pillar seems to have gone.

The ‘Braaid Circle’, a stone circle site with the remains of a Norse farmstead was also on the land of the Mount Murray estate until it was divided up in the last half of the 19th Century.

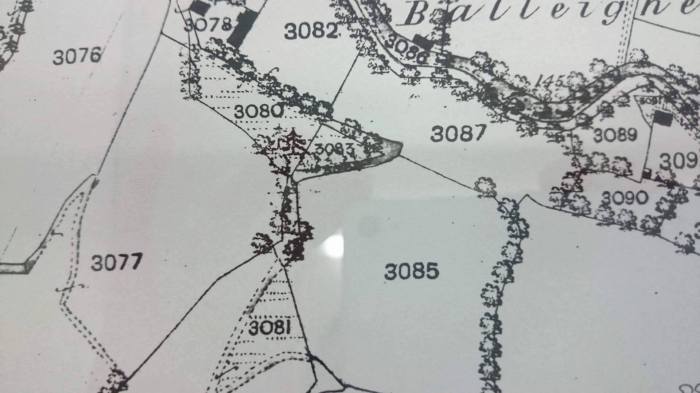

The first mention of the keeill at Speke, is on a Mount Murray Estate map (1800) which shows a small rectangular east-west aligned building in an enclosure marked as ‘old chapel’, this information comes from the Wessex Archaeology report for Time Team although I have had no luck trying to find this map myself in the MNH library. It is thought that John Murray (1755-1830), Fourth Duke of Atholl and a keen antiquarian, may have made a double ditched enclosure around the keeill site, possibly to protect it, in the process the enclosure cut through one of the graves. In recent times, the Mount Murray estate has become a golf club with a large housing estate in the grounds.

In the Ordnance Survey particulars on the site, it states;

‘ In a field to the immediate S.E. of Speke is pointed out the site of an ancient Chapel and Burial Ground. A number of stone lined graves are to be seen in the road running past the E. end of the field, and during the construction of the road a large quantity of human bones were found. There is no tradition regarding the spot.’ Authorities quoted are: Mr. John Corris; Mr. Hog g; Mr. Quine; Dr. Oliver, Douglas.’

At the time that Kermode was surveying the keeills, there were no visible remains at the site. In the Fifth Report (1918, Kermode), it mentions that Mr Richard Lace had examined fourteen lintel graves at the site and found them ‘of the usual character’ although he had found two adult bodies in one grave which was unusual, he estimated from the burials that the cemetery would have been around 200 yards in diameter. Richard Lace was headmaster at Santon school and an enthusiastic antiquarian who completed a number of surveys at Kermode’s request including the Sulbrick and Ballawoods keeill sites. There are a number of letters between him and Kermode in Kermode’s private papers and we are reminded that many others share the credit for the wonderful work of the Manx Archaeological Survey. Other than the mention of the lintel graves, there is no other information in the Kermode report.

In 1992 when the area was being developed there was a survey of the keeill site but unfortunately the records of this were not lodged with the MNH library so I wasn’t able to access it, the connected planning applications were unfortunately unable to be found. So, very little was known of this seemingly long ploughed over site and the stone could have become little more than a marker in a round of golf.

Until Time Team happened!

The Speke Keeill was excavated by Time Team and Wessex Archaeology and the results were aired on television in 2007. The following information on the Time Team dig I have used with permission from Wessex Archaeology and all quotes are taken from the full report on the dig which can be found here. The project had three aims;

To characterise the archaeological resource at the site;

To provide a condition survey of the site;

To determine the extent of the site.

Underneath the layer of turf covering the site, the team found the four walls of the keeill, built in Manx slate and granite blocks which had all fallen inwards, the wall had originally been supported by a layers of turf banked up against it on the outside. Underneath the collapsed walls, they found the original altar from the keeill, built of thin slabs of Manx slate and with the familiar white pebbles found both inside and around the altar that are often found at these sites. No floor covering was existent which may have meant the floor of the keeill could have been hardened earth instead of the frequently found stone slabs and the door was found to have been in the south west corner of the south wall. A roughly shaped square structure was found just outside one of the walls and was thought to be a ‘reliquary’, the inside was lined with white quartz stones;

‘This deposit was either packing for the lining (106) or positioned around whatever had been placed within the feature, perhaps a small box containing a piece of the founder’s remains. Following the abandonment of the keeill, the reliquary may have been opened and the relic removed to another location.’

It was found that after the keeill had been abandoned as a chapel, there was a period of disuse before the walls were possibly intentionally demolished or collapsed naturally. A slate slab incised with a cross was found which may have originally been a grave marker before being reused in the structure of the keeill itself. In one of the ditches was found an Ogham marked stone;

Ogham originated in Ireland in the 4th and 5th centuries where it continued to be used until about the 7th century. It continued in use longer in Scotland, well in to the 10th and 11th centuries, particularly in the Northern Isles of Orkney and Shetland where there was a mixing of the Norse and native Gaelic cultures along the Atlantic west coast of Britain. Ogham is notoriously difficult to date although the development of the script is known. The earliest form of ogham was written down the arris edges of stones or timber with lines or letter strokes scribed either side (Type I ogham). Later it was written on flat surfaces with a central line or stem used to imitate the arris edge, with lines scribed above and below this stem creating bundles of letter strokes (Type II ogham).

The Ogham stone at Speke is written in a form of Gaelic particular to the Northern Isles and dates from between the 8th century and the 12th century, the inscription reads;

‘BAC OCOICAT IALL’ meaning ‘corner/angle, fifty, throng/group’

It appears to have been doodling or graffiti rather than a formal inscription but was a very rare find. A number of slate slabs with crosses on have been found at the site of the years; an incised cross was found by an Officer Cadet Training party camping at the site in 1941 and Ross Trench-Jellicoe found a slab marked with a cross at the site when conducting a study of Manx crosses on the Island in 1981.

The graves were excavated and one was found to hold a small plait of hair; an unusual find as hair is rarely preserved from that date. Samples from three graves were sent for radiocarbon dating, these were found to all date from between the 6th and 7th centuries which made them pre-Norse and much earlier than the keeill itself.

The report suggests that the history of events at Speke Keeill is similar to that at Balladoole with a keeill being built within an earlier cemetery following the arrival of the Norse around the 9th century. This is a situation found in several other keeill sites on the Island including Ballameanagh Keeill, Upper Sulby Keeill and Keeill Woirrey, Maughold (Lowe 1987, 78-9). They were unable to find out the extent of the site due to time constraints but it is thought that Richard Lace’s estimate of the cemetery measuring 200 yards in diameter may have been pretty fair.

This excavation of the Speke Keeill by Time Team and Wessex Archaeology has brought life to this site and much has been learnt from their findings.

Modern technology and archaeological practice have advanced so much from the time of the Kermode surveys and one has to wonder what else would be learnt about early Celtic life on the Island if there was an unlimited resource of archaeologists and time to excavate the many ancient sites on the Island to this level. Wishful thinking of course.

So, next time you’re playing a round of golf at Mount Murray, consider those graves you’re walking over; in the Isle of Man, there is history everywhere.

More information on the Manx keeills.

Fig. 5. Walls of Keeill, Corrody, showing stone skirting.

Fig. 5. Walls of Keeill, Corrody, showing stone skirting.

Fig. 6. Cross-slab from Cabbal Pherick, Michael.

Fig. 6. Cross-slab from Cabbal Pherick, Michael.